Where Jack and Jill really did go up the hill

The joy of nursery rhymes

The best trivia is the stuff you bump into unexpectedly, those little facts that appear from nowhere and light up your day like an interesting old cove you've met in a pub. It happened to me recently in Somerset.

My partner and I had treated ourselves to a night away at Babington House, Soho House's pad in the country. (Not that we're members. We both work in the media, but it's not, as far as I know, compulsory. Or at least not yet. Anyone can go and stay there.) The hotel provide a list of recommended walks in the surrounding countryside. They also provide wellies. When I saw the sentence saying that one of the local hills was the one Jack and Jill fell down, I had to go and investigate.

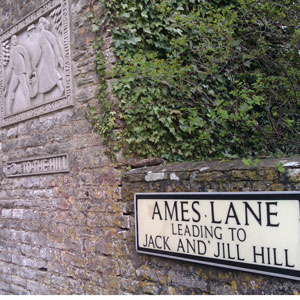

The hill, it transpires, is in the small village of Kilmersdon. A footpath leads up it, to the primary school. Pretty steep, but not too much of a climb - the schoolkids have to do it every day, after all. A sign at the bottom of the path (from Ames Lane) alerts you to the connection (see pic), then at regular intervals on the way up are little marker stones, each relating a line from the poem. At the top, in the grounds of the school itself, is an old well, thankfully disused by the look of it, but still in good nick.

A beautiful slate plaque on the side of the school relates the story, which is that in 1697 a local unmarried woman named Jill became pregnant. One day the presumed father, Jack, was hit by a boulder from nearby Badstone Quarry and died. Jill went on to have the child, but she herself died not long afterwards. Villagers raised the boy, ‘Jill's son', and this is supposedly where the common local surname Gilson comes from.

All very doubtful, as these stories always are, but charming nonetheless. The trivia behind nursery rhymes is always exciting, because it gives us an excuse to return to our childhoods. I was thrilled recently to learn that Twinkle Twinkle Little Star was written in Lavenham, a village near my home in Suffolk. Way more thrilled than if it had been Rule Britannia. (And certainly way more than if it had been the national anthem - when are we going to change that for something with a decent tune?) Similarly it brought a smile to the face as I climbed the hill outside High Barnet Tube station (for Walk the Lines) to know it was the hill the Grand Old Duke of York marched his men up and down.

The strangest things can remind you of this stuff. One night in a curry house on Brick Lane, eating chicken hunza (made with oranges) and lemon rice, I realised I'd accidentally ordered a meal symbolising the nursery rhyme about London's churches. There's a theory that Oranges and Lemons is all about the capital's public executions, hence the last line about chopping off your head. Then of course there's Pop Goes the Weasel, about pawning things to pay for your visits to the Eagle pub on the City Road (still there today). I've heard various explanations for what a weasel is. Some say it's a tailor's iron, others that it's rhyming slang for coat (‘weasel and stoat').

Whatever the truth behind all this theorising, surely part of our fascination with it is the reminder it gives of our younger days. The days when we had nothing more to worry about that how we were going to snaffle an extra Jaffa Cake without Mum noticing.

Books

Books Walks

Walks Quizzes

Quizzes Blog

Blog Magic

Magic